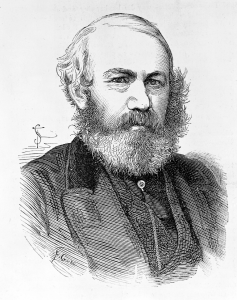

Sir Thomas Bouch

25 Feb 1822 – 30 Oct 1880

The second son of four children, Thomas Bouch was born at Thursby in Cumberland (now Cumbria) in 1822. His father, a retired sea captain died when he was sixteen. Two years after a brief period as an engineering apprentice in Liverpool, he entered the world of railway civil engineering by helping survey the route up the River Lune and over Shap Fell for the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway.

He took an Edinburgh office at 78 George Street which would serve as his business base for many years, and married in 1853. During his career in Lothian he became associated with nearly twenty Scottish railway projects both north and south of the Firth of Forth as well as several projects in England.

Bouch spent nine years as engineer responsible for this major North British railway project to shorten their main line from Edinburgh to Dundee and the north.

After the successful completion and opening of the bridge over the Tay in 1878 Queen Victoria used the route on her trip south from Balmoral in June 1879 and the North British Railway summoned Bouch to ride on the footplate of the Royal train. Three weeks after at the pinnacle of his career he was knighted at Windsor.

- Working with George Leather, a civil engineer in Leeds

- Working as an assistant engineer with John Dixon, the engineer of the Stockton and Darlington Railway on the railway being constructed up Weardale (1845)

- Taking up a job as manager of the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee railway in Scotland (1849)

- Working on the Darlington and Barnard Castle Railway (1854)

- Working on the South Durham and Lancashire Union Railway contract (1857)

- Working on the Eden Valley Railway (1858

- Working on the Cockermouth, Keswick and Penrith line (1861)

Sadly of course Thomas Bouch is best known for the spectacular failure he was responsible for at the end of his life – the Tay Bridge Disaster of 1879. As the designer of the ill-fated Tay Bridge, he was inevitably blamed by the Board of Trade Inquiry into the disaster, although there were strong suspicions that shoddy workmanship at the Wormit Foundry, where the iron girders were manufactured, may have been more responsible.

Broken in spirit, the man who had been knighted in recognition of his feat in building the world’s longest bridge, became a recluse and died of stress in October 1880, only four months after the inquiry reported.