Contact Details

Central Library

The Wellgate

Dundee

DD1 1DB

Opening Hours

| Day | Time |

|---|---|

| Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday | 9.00am to 6.00pm |

| Wednesday | 10.00am to 6.00pm |

| Saturday | 9.30am to 5.00pm |

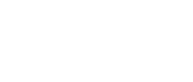

Mary Slessor

Dec 2 1848 – Jan 13 1915

Mary Slessor was born on 2nd December 1848 in Gilcomston, a suburb of Aberdeen, the second of seven children, only four of whom survived childhood.

Her father, Robert Slessor, originally from Buchan, was a shoemaker to trade. Her mother, from Oldmeldrum, was a deeply religious woman of sweet disposition, who had a keen interest in missionary work in the Calabar region of Nigeria.

She has been described as the “Mother of All the Peoples.”

In 1859, the family moved to Dundee in search of work. Mrs. Slessor became a member of the Wishart Church, named after the nearby Wishart Arch from which Protestant martyr George Wishart had reputedly preached to plague victims during the epidemic of 1544.

Mary’s father became an alcoholic and was unable to continue his shoemaking work. He finally took a job as a mill labourer. Mrs. Slessor was determined to see her children properly educated, and the young Mary not only attended Church but, at the age of eleven, began work as a “half timer” in the Baxter Brothers' Mill.

Mary spent half of her arduous day at a school provided by the mill owners, and the other half in productive employment for the company. Thus began a harsh introduction to the work ethic which was to dominate her life.

Young Mary Slessor

By the age of fourteen, Mary had become a skilled jute worker. The life of a weaver, no longer with the benefit of company schooling, was daunting by modern standards.

Up before 5.00am to do the housework, Mary worked from 6.00am to 6.00pm with just an hour for breakfast and lunch.

The photograph of a Dundee millgirl is not contemporary, but depicts a working life in which little had changed during the intervening years.

Fortunately, Mary had benefited significantly from her rudimentary education. More importantly, she developed an intense interest in religion and, when a mission was instituted in Quarry Pend (close by the Wishart Church), Mary volunteered to become a teacher. Later, the mission moved to Wishart Pend, where the Church still stands, and so began a formative period in Mary’s life during which she learned to cope with both physical and mental hardship.

The story is told of how she stood her ground against a local gang, who swung a metal weight on a string closer and closer to her face. This stalwart young woman defied the gang by obtaining their agreement that, should she not flinch, then all her tormentors would join the Sunday School class. Mary triumphed, and gained experience which she would later exploit in her contacts with even more threatening tribes in a distant land.

Mary Slessor

With young children

Strangely, although entranced by the accounts of work in Nigeria outlined in the “Missionary Record”, this courageous woman doubted her own ability to perform similar deeds, describing herself as “wee and thin and not very strong…” Eventually, however, she applied to the Foreign Mission Board of the United Presbyterian Church, effectively offering her life to the people of the Calabar region.

After a brief period of training in Edinburgh, Mary set sail in the S.S. Ethiopia on 5th August 1876, and arrived at her destination in West Africa just over a month later. She was 28 years of age, red haired with bright blue eyes shining in enthusiasm for the daunting task ahead. Some of the old hands in Calabar might have been excused for questioning whether she would last her first full year.

Portuguese mariners first visited the present day Nigeria in the 15th century to pursue trade with the kingdom of Benin, which straddled the land between Lagos and the Niger delta. By the year 1811, Wilberforce's great anti-slavery reforms started to take effect, and so the slave trade, which had disrupted society and government, finally began to crumble.

In 1861, Britain seized Lagos in order to preserve her trading interests, the first of a series of colonial initiatives which led to the establishment of the Nigerian Protectorate in 1914. When Mary Slessor arrived, she was to witness one of the most turbulent periods in the history of this process.

The culture and customs of her new flock are well described in Charles Partridge’s book, “Cross River Natives”. Witchcraft and superstition were prevalent in a country whose traditional society had been torn apart by the slave trade. Human sacrifice routinely followed the death of a village dignitary, and the ritual murder of twins was viewed by the new missionary with particular abhorrence. Her dedicated efforts to forestall this irrational superstition were to prove a resounding success, as photographs of Mary with her beloved children testify.

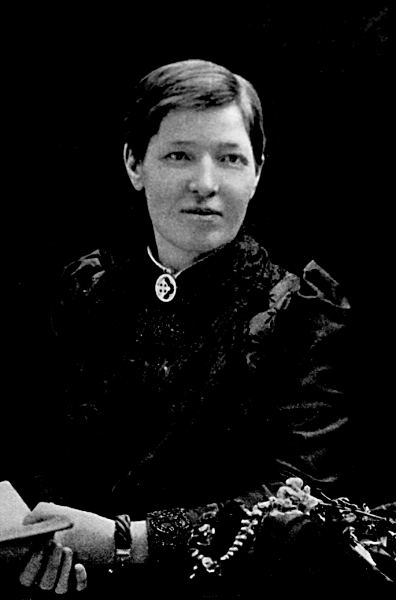

Mary Slessor

With the people of Ekenge

In this primitive society, women were treated as lower than cattle, and Mary was so successful in raising their standing in society that she may be considered as one of the pioneers of women's rights in Africa. She also became fluent in the Efik language, so that she might use humour and sarcasm to reinforce her arguments. Her voice was recorded by Charles Partridge on his phonograph, and you can hear an extract of Mary Slessor speaking Efik below. Unlike most missionaries, she lived in native style and became thoroughly conversant with the language, the culture and customs, and the day-to-day lives of those she served so well.

Unfortunately it was dangers other than those from aggressive natives and wild animals that faced missionaries from a relatively healthy Western European environment. It was not until 1902 that Sir Ronald Ross was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work on the Anopheles mosquito and its role as a host for the deadly malarial parasite. This knowledge was too late for Mary Slessor and her colleagues. Like lambs to the slaughter, they came to a country with its river mists and overpowering heat, where diseases and infections were legion, and they succumbed in their hundreds to the very fevers from which the modern traveller is mercifully spared. Their average life expectancy was just a few years, and those who survived and returned home often endured recurring fevers and ill-health for the rest of their lives. In letters reproduced here, Mary bravely makes light of her experiences, but the horrors of forty years of debilitating suffering may be clearly discerned through the surface humour and stoicism. In the early years of the 20th century, some remedies and precautions were becoming available, and Mary provided vaccination against the dreaded smallpox, and set up mission hospitals for treating illnesses and injuries suffered by the native peoples.

Mary’s dedicated work with the people and her almost total integration with them culminated in an official request by the Governor that she combine her missionary activities with an administrative position as a Member of the Itu Court. Her letters to Charles Partridge chronicle this period of colonial expansion. Roads were being driven into the interior, and military expeditions were starting to make use of motor vehicles. Untold dangers faced all those involved in these hazardous enterprises, and Mary Slessor, though ever keen to discount her own perilous situation, retained a pragmatic attitude to the dangers facing lesser mortals. In one letter she urges that the expedition should include a “Maxim” (machine gun).

She was constantly urging the Foreign Mission Board in Edinburgh to finance extensions of her work in the interior. The trading markets which she had enthusiastically encouraged attracted people from far afield, and her attempts to reach out to them were the natural consequences of these contacts. Gradually the money was forthcoming and, as new missionaries took over responsibility for the posts vacated by Mary, she was able to move ever further into the heartland. Her courage in braving the hostility provoked by these incursions is legendary.

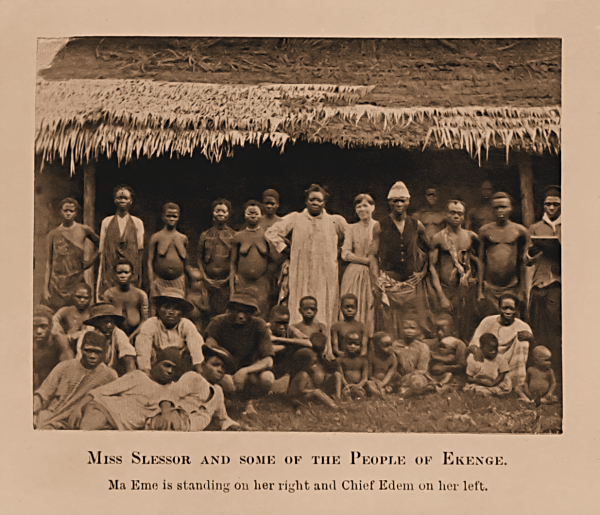

Mary Slessor

In later life

Mary’s life between 1906 and 1912, was a struggle between ill-health, and her most strenuous duties – court sittings, teaching and preaching, palavers with native visitors. Once, after ten hours in court, she returned home to find fifty visitors waiting for advice and it took her till midnight ‘to straighten out their troubles.’

When she became thoroughly ill, she consented to travel to the Canary Islands, and rest there as she could not rest where she was known. On her return, wonderfully restored, the doctor’s report of her was: ‘Good for many years – with care.’ With the best possible will to take care of herself, however, old habits of entire selflessness could not be broken through.

She went on with most of her ordinary work – except that of the court, which she gave up – she visited the centre at Akpap, meeting crowds of her old friends of Okoyong – some of her rescued babies grown into healthy, happy young people – and she conducted a religious service with a congregation of four hundred.

For two more years she wrestled on and on, meeting the same old difficulties in her own original ways, still travelling up and down the rivers, still keeping a little home where her native ‘children’ were cared for – and then came a last shattering blow – the Great War of 1914.

It was August – strange awful days in Europe, the first week after the Declaration of War – but it was not till August 13th that the news reached the Calabar Mission Field. It was the neighbourhood of the German territory of the Cameroons that brought fear to the European settlers there; fear for their settlements and work rather than for themselves. Miss Slessor’s health suffered greatly from the strain of anxiety but her fighting spirit rose, ‘Oh! if I were 30 years younger, and a man’, she cried.

The recurring illnesses and general hardships which she faced as a matter of course all took their toll on this redoubtable woman. By 1915, her physical strength had greatly declined, and the woman who had once thought nothing of all-night treks through the rain forest was finally reduced to travelling in a hand-cart propelled by one of her assistants. On the 13th January 1915, after an excruciating and prolonged bout of fever, Mary Slessor died aged 67. Five of her native girls were with her, and the mission workers nursed her by turns. She suffered intensely from thirst and utter weakness: ‘O God, release me’, she was heard to say. On January 12th her strength was swiftly ebbing, her breathing difficult; the end came gently in the very early dawn. In his biography of 1980, James Buchan described her as the “Expendable Mary Slessor”. Expendable she may have been, but few have given so much of themselves to so many, and under such appalling conditions.

The grave of Mary Slessor, marked by an imposing cross of Scottish granite, is in the heart of the country she served so well. She was accorded a state funeral and, in 1953, the new head of the Commonwealth, Elizabeth II, made her own pilgrimage to the graveside. Mary Slessor is still remembered in Dundee, as in her adopted homeland, and there is a growing world-wide interest in her work. The finest tribute was from those of her own who knew her best. To them she was “Mother of All The Peoples” or, more simply, “Ma”.

There seems no need to try to sum up the results of her work; as we read of it we feel indeed that the best part of it could not be described or expressed in any way. Her amazingly wide and deep influence was revealed to some extent after her death by the mass of letters she had received. It seems as though none came into contact with her without a deep impression of her simple, joyous, loving humanity. She is a beautiful example of the beautiful saying, ‘To have love is to work miracles.’

- In 1923 a stained glass window was dedicated to Mary’s memory. This now resides in the café in Dundee’s McManus Galleries. There is a also a stained glass window dedicated to Mary in All Saints Church, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire.

- A series of banknotes issued by the Clydesdale Bank (now withdrawn) featured a different design for each denomination, each depicting a notable person from Scottish history. The £10 note featured an illustration of Slessor’s work in Calabar (Nigeria) including a map of the area and a lithographic vignette depicting her work with children.

- The Mary Slessor Foundation aims to continue the work of Mary Slessor, albeit in modern form.

Mary Slessor Memorial Window

The Café, The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery & Museum

Front

Back

Clydesdale Bank £10 Note

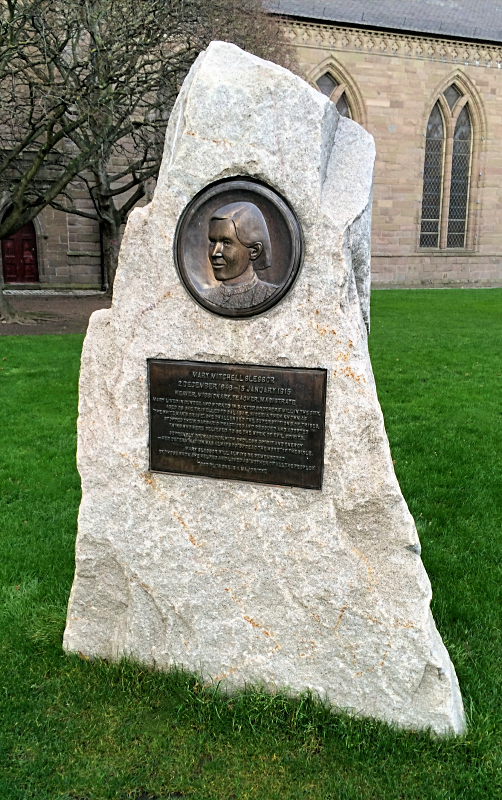

Granite Memorial

Unveiled 13 February 2015, Steeple Church, Dundee

The collection of Books and Letters and Slessor Source Material in Dundee Central Library's Local History Centre and the collection of letters and articles in the City Archives may be viewed during the normal opening hours of the Department. 24 hours notice is required, and readers must satisfy regulations governing conservation and security of these materials.

Suitable evidence of identity is required, and Dundee City Council reserves the right to refuse access to the materials, or to provide surrogates. Other letters and personalia concerning Mary Slessor, as well as a permanent display, can be seen at the Leisure & Arts Department, McManus Galleries, Albert Square, Dundee DD1 1DA

Transcripts of the letters were prepared and edited by Leslie A. Mackenzie and Ruth E. Riding. Dundee City Council gratefully acknowledges the substantial contribution made by these volunteers.

List of Books and Letters

The small but rich collection of Slessor correspondence in Dundee City Archives, consisting mainly of Mary’s warm communication with Miss Crawford, (an administrator and friend in the Free Church of Scotland), complements the larger collection held in Dundee Central Library of her letters to Partridge, a colonial administrator. A descendant of Miss Crawford’s family in Aberdeen generously decided to place the letters in Dundee City Archives for safe keeping in 1993 but their comparatively recent discovery means that their existence is not widely known.

Mary’s humour is evident from her first manuscript letter of 1901, in which, having been asked for her date of birth for annuity purposes, she states that the document giving the year has been eaten by ants, but that she hopes to escape all obligations to any annuity fund by being able to “hold her small fort to the last stage of the Pilgrimage”. These were prophetic words, for Mary’s unfailingly cheerful correspondence with both Crawford and Partridge were to continue, despite illness, delay and frustrations, until shortly before her death in harness in 1915. Her last letter, in December 1914, to Miss Crawford – by then her ‘very dear friend’ – is littered with scriptural references, and combines testimony to her faith with concern about conditions in the trenches in Europe, references to the war in Cameroon, and the statement that she is sending her requests via the ‘heavenly wireless’.

Another complementary factor in Mary’s two series of correspondence with the two administrators – one colonial, one ecclesiastical – shows the ease with which she dealt with all levels of people, and the eye that she had for detail. Her writing might be hurried and her expression hampered by a lack of formal education, but she consistently shows herself to be a highly competent and intelligent administrator with clear objectives. The Crawford collection is rounded off by a number of miscellaneous prints of articles which clearly indicate contemporary interest in her activities, trials and successes.

List of Articles

List of Reference Works in the Local History Centre of Dundee Central Library

Boyd, James

Mary Slessor Memorial Window and Corner Central Museum, Albert Institute, Dundee, 1969.

Compiled from notes of T. M. Davidson. D. 6823

Buchan, James

The Expendable Mary Slessor. Edinburgh:

St. Andrew Press, 1980. 0 7152 0438 6. D.20885, 21458

Buchan, James

Peacemaker of Calabar:

The Story of Mary Slessor. Exeter: Religious and Moral Education Press, 1984 D. 30259, 30260, 30261, 30262

Christian, Carol and Plummer, Gladys

God and One Redhead: Mary Slessor of Calabar.

Hodder and Stoughton, 1970. D.6832, 67133

Church of Scotland, Overseas Council

Mary Slessor of Calabar.

Church of Scotland Overseas Council, 1978. D.15496, 15502

Davidson, Thomas M.

The Mary Slessor Memorial Window:

Descriptive notes and short biography, 1924. D.3850, 4968, 7657, 32684

Dundee Corporation

City by Glen and Sea. Dundee:

Herald Press, 1962. D.3795, 3810, 3846, 3847

Ellis, J. J.

Mary Slessor, the Dundee Factory Girl who became a devoted African Missionary. Kilmarnock:

John Ritchie Ltd., 1920. D.3900

Eme, Nwachuku

From Heathenism to Christianity. March, 1958. D.8380

Grampian Television

Script of the programme on Mary Slessor in “Great Scot” Series No. 19.

D.8377, 8378

Heroes of the Cross

Pandita Ramabui Mary Slessor: Rasalama, and Heroes in Madagascar. London:

Marshall, Morgan and Scott, 1933. D.4059

Knock, Esther E.

The Missionary Heroine of Calabar; a story of Mary Slessor,1956.

D.3722

Livingstone, Mrs. W. P. comp.

The Mary Slessor Calendar. London:

Hodder and Stoughton, 1933. D.1395, 12406

Livingstone, W. P.

Livingstone, W. P.

Mary Slessor of Calabar: Pioneer Missionary. London:

Hodder and Stoughton, 1915. D.18029, 9328

4th edn., 1916 – D.30366, 9329, 3859

10th edn., 1917 – D.9330, 4334, 4770, 30819

Livingstone, W. P.

Mary Slessor the White Queen. London:

Hodder and Stoughton, 1933. D.20567

Livingstone, W. P.

Livingstone, W. P.

The White Queen of Okoyong… Mary Slessor. London:

Hodder and Stoughton, 1916. D.12405, 1501 1967 paperback edn. – D.1368 1933 edn.– D.20567

Luke, James

Pioneering in Mary Slessor’s Country. London:

The Epworth Press, 1929. D.31801

McFarlan, Donald M. Calabar:

The Church of Scotland Mission, 1846–1946.

Thomas Nelson and Son Ltd., 1946. D.4606, 4061

McFarlan, Donald M.

McFarlan, Donald M.

White Queen. The Story of Mary Slessor. London:

Lutterworth Press, 1963. D.3886, 4265

Miller, Basil

Miller, Basil

Mary Slessor: Heroine of Calabar. Grand Rapids, Michigan, U.S.A.:

Zandervan Publishing House, 1966. D.4495

O’Brien, Brian

She had Magic: The Story of Mary Slessor. London:

Cape, 1958. D.6381, 4163

Slessor, Daniel MacArthur

Reminiscences of Miss Mary Slessor.

Typescript. D.8380 bound with Mary Slessor – Pioneer Missionary. Typescript. D.8380

Slessor, Mary

Photocopies of letters. D.21762

Stein, Rev. Jock, Hudson, J. H. and Jarvie, Thomas W.

Let the Fire Burn…a Study of R. M. McCheyne, Robert Annan and Mary Slessor. D.15545, 15546

Other

Tape cassette recording of Miss Slessor’s voice.

Illustration of Memorial Window. F.1

Obituary in Dundee Yearbook – 18th January 1915 at Calabar.

Resources in the Local History Centre are for reference only, and are not available for loan. In certain circumstances, photocopies or digital scans may be provided according to the prevailing scale of charges from Local History. Alternatively, researchers may find that copies of cited works are available through their national inter-library loans service.