Dundee’s Maritime Pasts and Futures

“for no one knows what to do or where to go for the best, while time wears on apace.”

Alexander Smith, Chief Engineer on S.S. Camperdown, 1861

Dundee’s Maritime Pasts and Futures is a project exploring the city’s relationship with the River Tay by looking at our histories of whaling, the ways we interact with the river now, and our hopes and fears for the future in the era of climate change.

The Tay is Scotland’s longest river, flowing a 119 mile course from Ben Lui in the Highlands towards the Firth of Tay where it enters the North Sea. Dundee has grown around it, from early fishing settlements by the Stannergate to the city we know today. The city’s growth has also changed the shape of the riverbank, as people have built out into the river to make land for the railway and to construct docks which have later been filled in. The waterfront continues to change, with new buildings and developments in progress – and predictions suggest the next fifty to one hundred years will see further dramatic changes as water levels rise and some of our ‘reclaimed’ land returns to the water. For centuries, the Tay has been a route in and out of Dundee for people, animals, ideas, and materials, as well as a source of food, work, and connection to place for the people who live near it.

Dundee Libraries’ Local History collections include several logbooks from whaling ships in the 19th and early 20th centuries. One of these, kept by Alexander Smith on the S.S. Camperdown in 1861, records daily life on board the ship, as well as reflections on the whaling and sealing industries and the experience of life at sea. Project volunteer Stuart Will has digitised the book from microfilm and completed a full transcription of the first voyage, a sealing trip to Greenland.

On this web resource, which has been supported by the Public Library Improvement Fund, we will share Alexander Smith’s stories from life on board the S.S. Camperdown in which he speaks about his hopes, fears and observations, alongside other stories and images about Dundee’s maritime connections. We hope these stories, and Cara Rooney’s artwork illustrating discussions which took place at a Maritime Pasts & Futures event in March 2024, inspire you to reflect and start conversations about the topics they touch on.

Find books related to Dundee’s maritime history and the River Tay in the library’s collections:

Voyages

Alexander Smith’s Diary

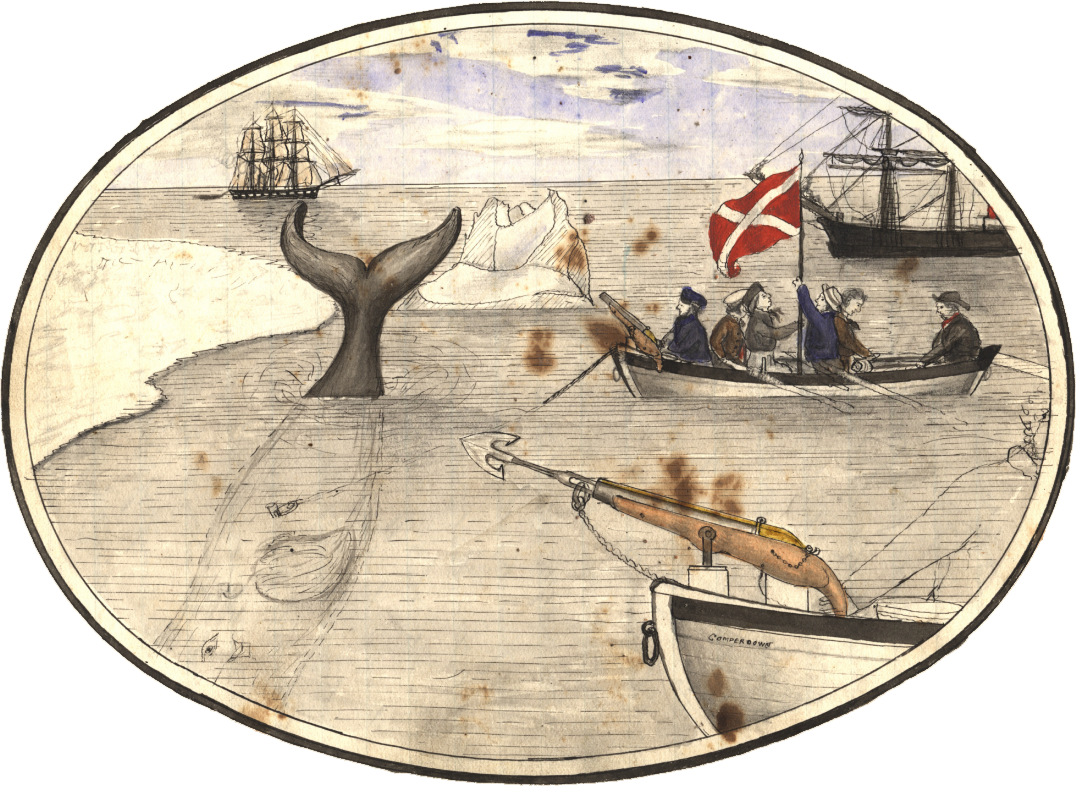

Whaling was one of Dundee’s major industries during the late 18th and 19th centuries. Over the years, many ships sailed from Dundee to the Arctic in search of whales, often stopping off in Stromness or Lerwick to pick up additional crew and supplies. Whales were big business: whalebone could be used to make umbrellas, corsets and other goods, but the biggest reason for hunting these creatures was their blubber. Once processed into oil, this could be used as fuel for lighting and heating, as well as in making soap. The first commercial whaling voyages left Dundee in the 1750s. After a century of hunting whales, they had almost disappeared from waters near Scotland, and whale populations were in serious decline in the Arctic. The whaling industry was likewise in decline – until textile manufacturers in Dundee discovered that whale oil was by far the best material with which to soften rough jute fibre to make it suitable for processing. Demand for whales rose once again, and Dundee's whaling industry began to grow. Commercial whaling continued longer in Dundee than anywhere else in Scotland due to its links with the jute trade. As well as whales, seals and walruses were also hunted for their blubber.

On Wednesday 21st February 1861, SS Camperdown prepared to set sail from Dundee harbour for Greenland on a sealing voyage. Among those on board was Alexander Smith, chief engineer. Smith kept a journal of the voyage, documenting daily life on board the ship, the weather and the places they travelled to, as well as reflecting on the uncertainty of life at sea and the unpredictability of their mission. Smith also painted scenes to illustrate the Inuit people he and other Scottish crewmen met in the Arctic, and hunting scenes from the voyages.

The book has been digitised from microfilm by Local History volunteer Stuart Will, and a PDF is available here:

Download a PDF Read the Transcript

Departure – and an incident in Dundee Harbour (p. 1-5 of the book)

On Wednesday 27th of February 1861 all was bustle and activity on board of “S. S. Camperdown” agreed to sail from Dundee Harbour for the prosceqution of the Northern Seal fishery. She was one of 5 auxilliary screw steamers destined for Old Greenland that year and her second year in the trade. She was built by the firm of Stephen Shipbuilders in Dundee in 1860 and supplied with engines of 70 nominal horse power by Messrs Gourlay also of that town, by contract and being unsuccessfull the year previous. Some slight manifestation of anxiety was displayed by all concerned, and the community at large as to her future career & fortune for she was really a noble vessal and well provided. Accordingly by the ship’s Articles all Hands had to be on board by twelve o’clock on that day and ready for Sea. Accordingly I Shaped my course to the West Dock, where she was moored to the quay, for we had to steam out into the river and consequently required a little time to put everything to rights & get steam up.

The first I met on deck was our Captain Will Bruce who to some extent was part Owner, nevertheless quite free from the avarice & meanness so prevalent amongst our captains & ship owners, being a man of a free & liberal disposition, enterprising and of a decisive, masterly turn. His motto is what you do, that you do it well and spare no necessary cost or time. Having so far noticed the vessel & her master allow me to introduce myself as Chief Engineer, second voyage & ship, having been in the capacity of second engineer in the “Wildfire” the preceding year to Captain L. B. Walker and proved succesfull.

After the usual compliments of the morning, our Captain informed me he intended if the muster of the crew was good he would in all probability go right out to sea and to have steam ready by half past two the tide answering about 3 O Clock P.M. So down stairs I went in order to run up the water in the boiler, and so prepare ourselves to be in readiness when the time for our action should arrive. Light in spirits for I loved the life we were about to [?] on and yet I felt a little thoughtfull from various causes, leaving my home and father’s house besides a few faithful, dear friends, bound by inseparable ties of affection, together with the responsibility devolving on my sensitive constitution, however the full rigour of youth was mine, and thought was soon, soon abandoned for active duty.

In due time my force of men arrived and work went on smoothly & cheerily and after little odds and ends were settled I contented myself all was right went home to dinner, although I did not harm it much, bade father, mother, sister and brothers good bye, and hurried back to my future abode with my stomach empty and my heart full and found everything as I could with it, we were now in all readiness and expectations, and a goodly number of the respectable people of Dundee now stood upon the quay waiting our departure the very steam would be confined no longer and likewise expressed a desire to be off, it was now verging on four o’clock when they began to loose her moorings and many good bye’s were then spoken with words of comfort and consolation, handkerchiefs were agitated by fair delicate hands in token of adieu, or a lover’s parting kiss observed as a pledge of truth and mutual understanding, with various other demonstration on the occaision of separation and a fellow as if to eclipse the whole, his feet going farther than his judgment adroitly drops into the dock along side of us from the quay then arose the hue & cry of a man in the water, and a simultaneous rush of the crowd nearly proved fatal to a few more of their number, during which he was got safely out & we moved quietly off amidst such cheers as is seldom heard, after waiting at the Ferry roadstead until the train should arrive, we again moved on with a light wind in our favor it was now about 8 O’clock and close on nine ere we parted with the Pilot for we had to wait some time for the Pilot Cutter, and now clear of all obstruction we once more shot ahead, and next morning found us past the entrance of the Moray Firth, it was a rare and lovely morning and the gentle easy motion of our ship as she glided along with the dense columns of smoke at intervals curling in the air, formed a pleasant contrast with the rising sun, tipping the rolling waves with a golden hue, yes, it was sweet and pleasant and the fragrant morning air put me in remembrance of my Breakfast but my contemplations were here cut short, I had also something else to engage my attention which I was near forgetting, and that was my engines.

On a difficult year for seal fishing (p. 27-29)

We have now been pretty well north in this country and as far as gone, no satisfactory or beneficial result has been obtained, tending only to make our hitherto imperfect ideas yet more conflicting and confused, being the opinion of a great many masters in our Greenland fleet. Judging from the appearance and casual condition of the country (i.e. the ice) there will be no good done this season, or in other words very few if any seals will be found by the ships here for this year, and still an unremitting search must be continued, for no one knows what to do or where to go for the best, while time wears on apace.

It is hard knocking about here, when in earnest or on eager search, I could scarce give you anything like a definite description of it, first seeking north things not being in a suitable condition, about ship is the word, and run south again, by the pack edge or edge of the main body of ice, perhaps descrying a fine lane or light of water in the interior and certainly prudence urges on once being sensible of seeing to use the phrase, what it is made of, then up steam and batter away amongst the detached mass which seems to bar all further progress or nearer approach, once inside each nook is carefully scrutinised while we make a circuit along its edge, feeling quite at ease, that nothing more remains best to give it up for a bad job, and come tumbling and rattling out again, in case of a night frost which would effectually confine us within said limits which if far from our wishes unless the seals took a fancy to pay us a visit whilst there, could we only ascertain their whereabouts we would be so condescending as to save them the extra bother, if they are actually here on the ice (and not as some has supposed) taken the air for it. I am somewhat surprised nobody has seen them as we have good reason to know in our perigrinations, receiving them every two or three days, I mean the equally unfortunate vessels from which I submit the following that no vessel, with whom we have had communication, we included, has yet ascertained or been at the spot where the seals are located, this season and hence the impossibility of catching them, or seeing them, which must take place first previous to catching them.

Prior to my conclusion, I mean to offer an excuse, exculpating us from censure on our unsuccessfull voyage if so it may end as it has every appearance of so doing, in the following

Seal fishing, in common with most other chances, probabilities, on speculations, hase its own peculiar laws, modes, or reliable rules and theorys, carefully deduced, and founded on the practical experience of a long series of years and principally hinging on the, texture, form, position, and general appearance of the ice as found at the time the old seals are supposed to take the ice, together with the winds, which has been prevalent and which in some way affect the position of the ice, and the winds in prospect that will in all likelihood affect it still more.

A lively discussion between crewmates (p. 32-34)

Surely this cannot be Greenland cries one man to his mate, on a fine sunny morning while basking himself in the sunbeams on deck.

The person he had just addressed, turning slowly round, from his first contemplation of the days probabilities was one well suited to answer from his long experience. The other and his juniors sceptical question looked at him with one of those whimsical, droll expressions, peculiarly the privilege of seafaring life.

Well now where did you think you were eh: hang me, if the fellow ain’t got out of bed before he is half awake go down and, oh interrupted the young man thus rebuked, twas only because I didn’t expect to see such fine weather out here I said that. Well, now you’re a precious chick. Surely: Why did you think, you great blockhead the sun could only shine nowhere but on Fife, well I’m blessed.

No, persisted the other but from any account I could get, it was awful cold out here, and look at the difference to day. Ho ho you may as well look at the difference tomorrow. Man – alive – do you know what you are talking about, wait till the first nor' easter sets in, I’m blowed if old nick himself will get you on deck. I well remember once of being wintered in the “Queen” I think in ‘54 for exercise and fresh victuals we use to take a day to hunt the deer over the snow, well look ye the frost was that hard, now I’m telling the truth, while taking off my mitten to put a cap on my gun, d--n me look sore if I haven’t had my hand frost bit, you fellows don’t now what frost is, no there was only 3 of our whole ships company that was not frost bit or bad with scurvy, that’s the spot to take a trial off where 16 of us died that three months.

I like folk to speak with some sense, d---d easy for the likes of you, whenever it comes the least bit of cold, shirk away below out of sight or else get muffled up to the eyes in your mother’s shawls like a scarecrow in a tatie field. But I say Bill how would you like getting lashed to the masthead for twenty four hours eh, shipmate, fine day and altogether, his discourse was here cut short by the order to slack away the head sheets, and so for the present ended this nice dialogue.

A week of weather on the Arctic Ocean, April 1861 (p. 40-41)

Tuesday 2nd April, very mild clear morning, under steam from 7am until 3pm when it came a heavy thickness which caused us to stop.

Wednesday, still mild, thick weather, very cold towards night

Thursday, thick snow, wind Nor[th] East

Friday, very clear, and very cold under steam all day, searching South

Saturday, cold thick weather steaming all day, wind toward evening from Sou[th] West, sighted Jan Mayen Island.

Sunday, extremely cold, wind N.W. and very intense frost all day, (Barber Flying)

Monday, most intense frost, nearly all the pipes containing water frozen, and a few burst pipe leading to pressure gauge frozen, tube of ditto burst, indicating a pressure from congealment 10 lbs on the square inch, although 2 furnaces were kept in active combustion night & day, raised steam and steamed all day North

Tuesday 9th, South East gale & thickness

From the preceding statements it will be readily seen at a glance, the liability we are under to changes of weather and atmospherical inconsistency arising therefrom and the ignorance and uncertainty we are in as regards its approach as it totally changes in the lapse of a few minutes from one extreme into the other, and also the disagreeable effects it produces, some of them very provoking what is here termed “Barber” is the minute frozen particles (arising from this thickness or moisture) floating throughout the whole atmosphere and scarcely discernable until it accumulates, which it does very readily to hair or ropes until they become thickly coated by it, and the beard soon assumes the appearance of being soap’d previous to a shave, hence the phrase (“the Barber”)

And putting me in mind of a curious story, the authenticity of which I cannot vouch for, and if my ink would be so obliging as to remain a fluid, I might venture to transmit it to paper if memory permits

Have to dissolve the ink at a fire occasionally.

Alexander Smith celebrates his 24th birthday and reflects on hard times

Well I declare here is my 24th birthday anniversary past, exactly one week ago Saturday 13th April and the first time I am sensible of it is as I write that ought at least to be a tumbler of punch for me tonight as I can’t get it sooner, but I reckon it will do - the rub is when am I to find it be found it must, on such an occasion it is wholly indispensable, when he serves himself, so here goes and it is our candid opinion (that is the doctor and one or two more) that a sprinkling of the fair sex would be necessary to keep us in order & good humour, (them as the grand poet truly observes

Will neatly brush our Sunday cl’oes

And with them to the pop they goes

While we poor mortals never knows

Woman, charming woman O

“twasn’t” I that wrote this “ere specimen”.

We don’t know how you are getting on at home but can assure you we are doing wonderfull well in the meantime here, and with a will, quite a respectable private concert of our own in the engine room and specially select are the audience the lot of us wishing we were home, very early separating after the usual toast of

To “the wind that blows”

To “the ship that goes”

& “the lass that loves a sailor”

& sentiment

The seals may break our fortune, but will never break our heart.

We can manage that is upwards of 70 hands can pick up 3 or 4 of the critters in a day, not bad work at all, already we have a better voyage than they had last year after all, as we have upwards of 2 dozen, while they had only 19 last voyage, we have one comfort the bad news will be home before us, and the panic somewhat subsided ere we arrive, a deuced bad job for the town certainly and Peterhead especially, depending as it does on the seal and herrings fishings the poor place will become ruined as 28 vessals from there all unsuccessful is too much for it to bear.

Scrimshaw

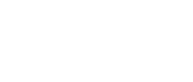

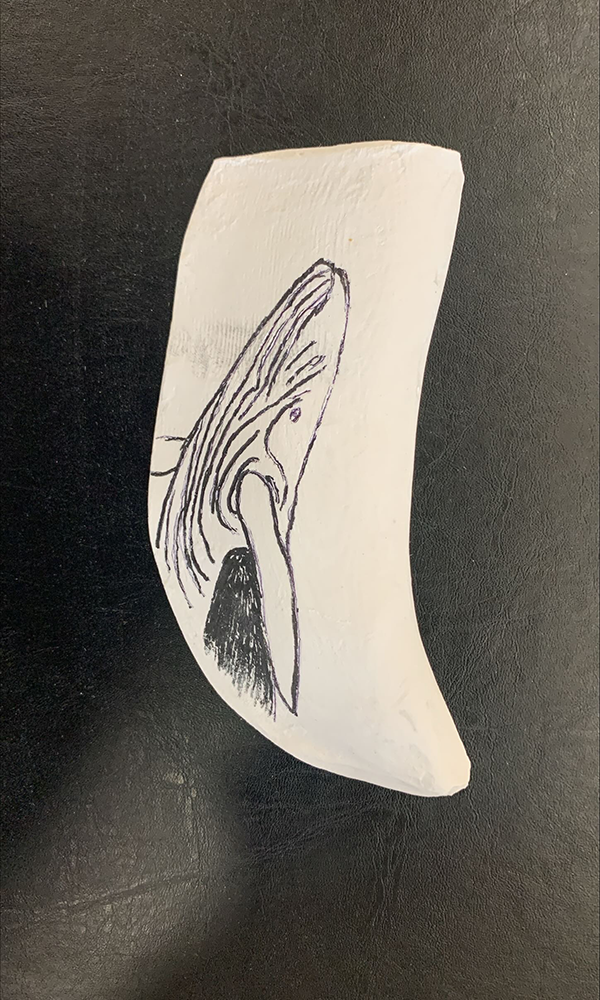

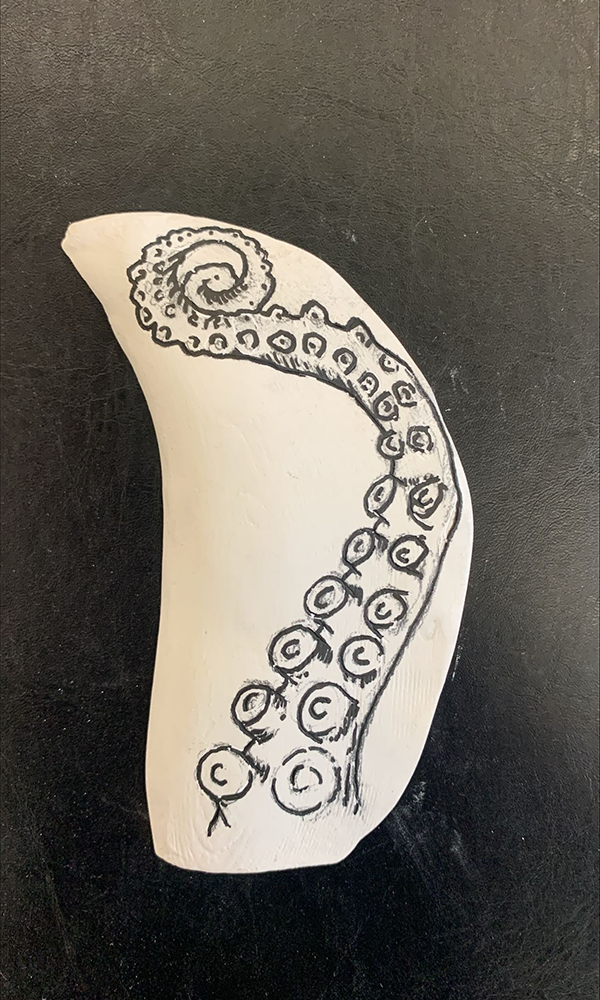

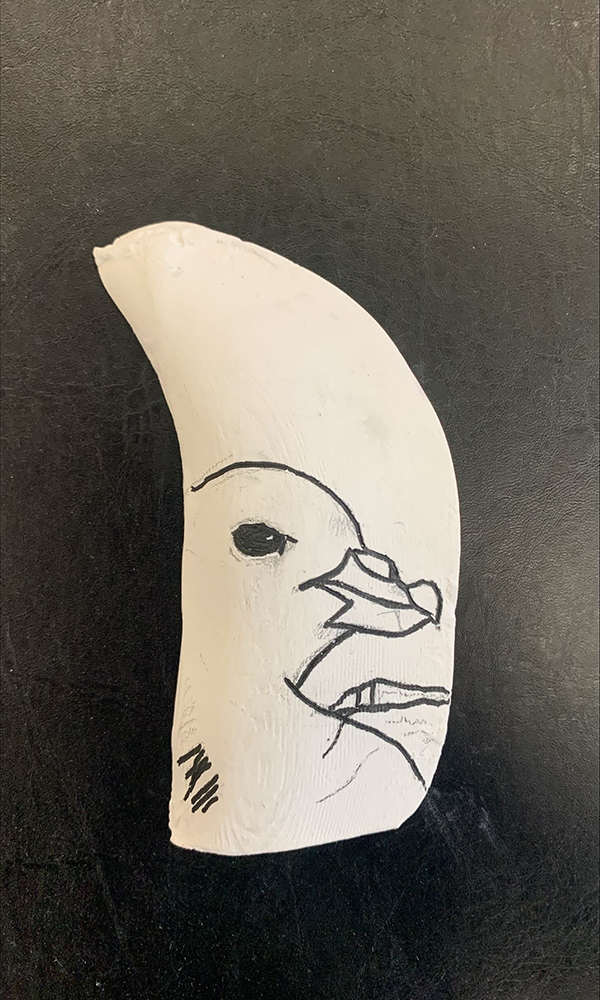

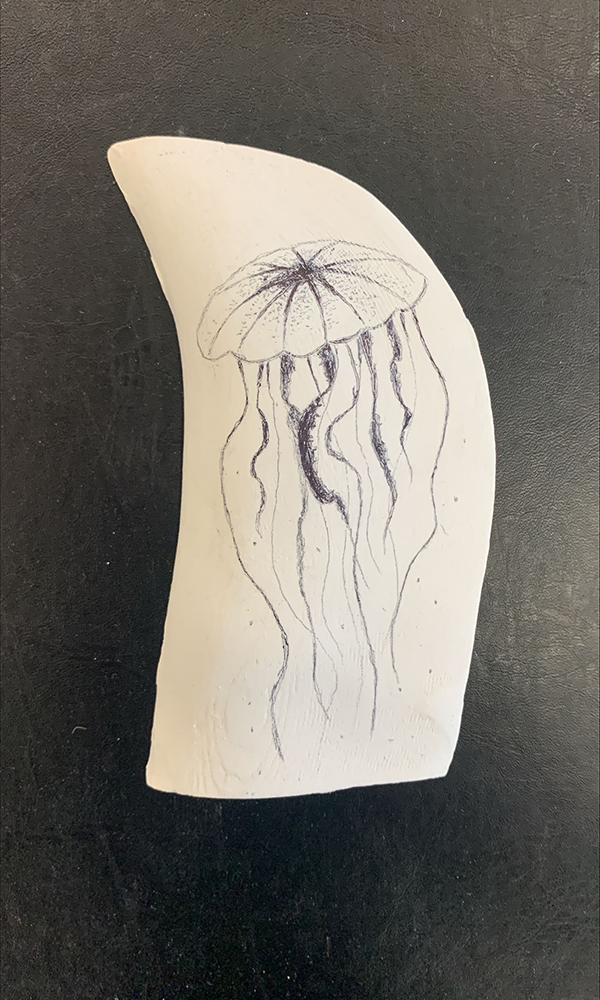

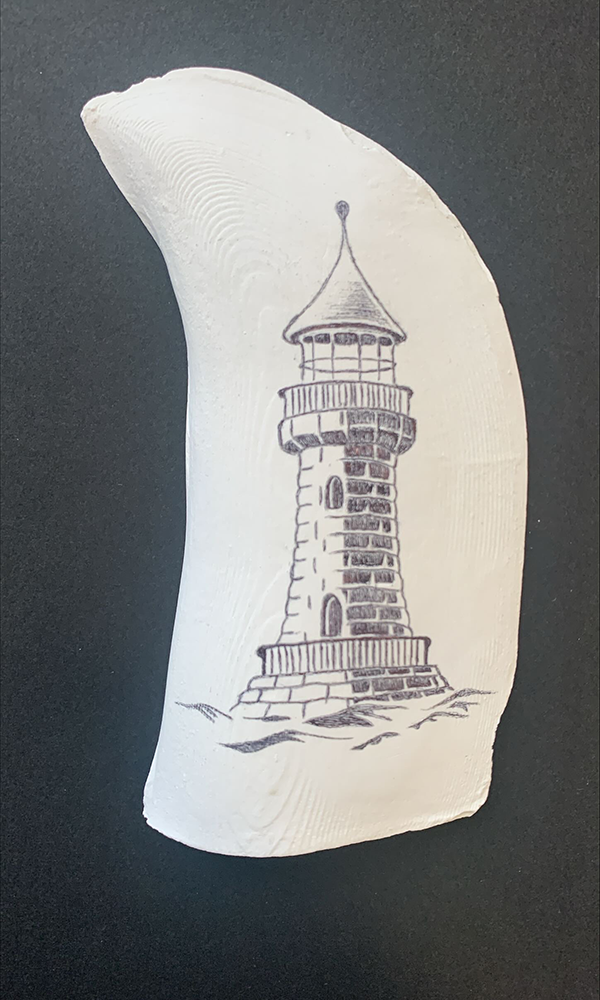

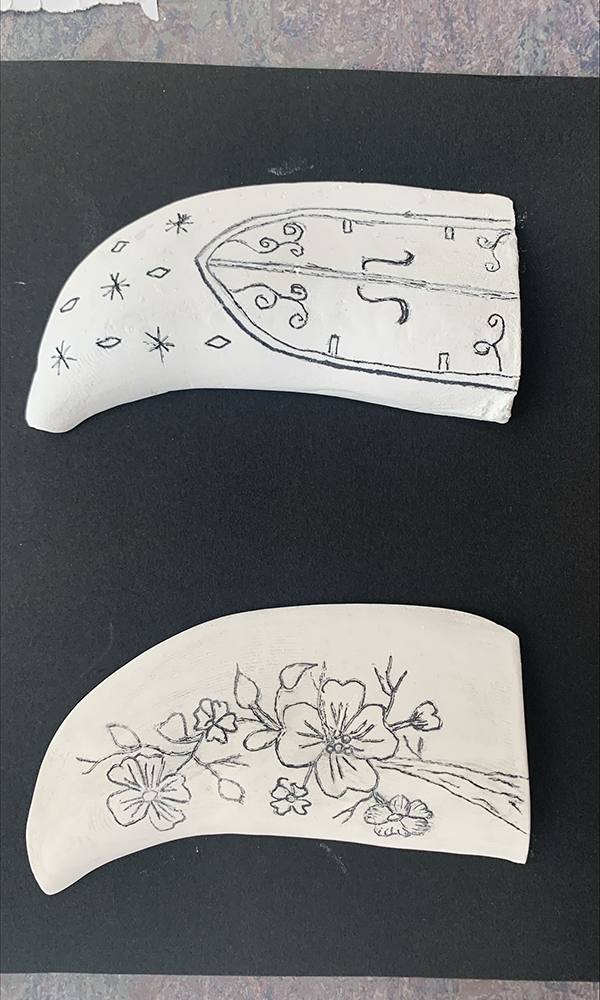

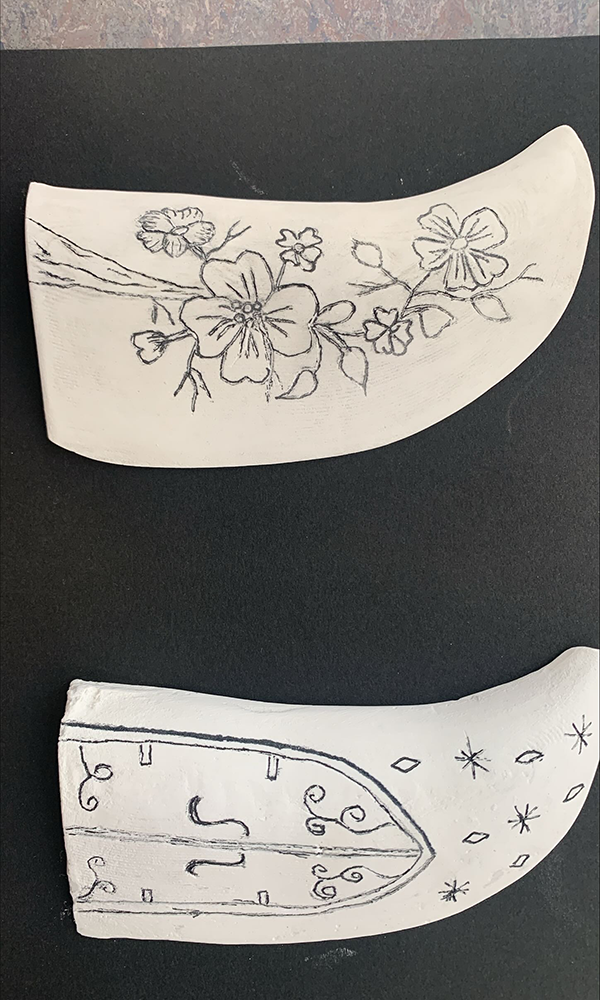

Scrimshaw – the practice of engraving illustrations onto whales’ teeth – became widespread in 1815 when a surplus in whale teeth caused their value to drop. Whaling ships’ crews began to use them as a canvas to create art inspired by their experiences at sea. Scrimshaw illustrations were illustrative and decorative, often depicting nautical imagery, words and emblems. An image would be etched onto the whale tooth with a carving knife, after which an ink would be applied to reveal the etched image. The image can be seen and felt. Scrimshaw is very fragile and would often be stored in barrels of oil on voyages.

These images show modern scrimshaw designs created at a workshop led by Niamh Coutts at the Local History Department, during which participants learned about the history of whaling in Dundee and the practice of scrimshaw, using this as inspiration to create these poignant images.

The Changing Shoreline

Dundee’s waterfront changed often in the 19th century. The river ran close to the edge of the Magdalen Green before the Dundee-Perth railway line was constructed. Before the 1820s, the town's main harbour was located by the Craig Pier, next to Yeaman Shore, but it was too small to accommodate the volume of trade Dundee aspired to, and the city’s industrial growth was supported and encouraged by a steady eastward expansion of new docks built out into the river. Dock Street connected them all and was the site of the Exchange Coffee House (now 15 Shore Terrace) and the city’s Customs House, in its day the second largest in Scotland. In the 1840s, railways improved trade connections in the area even further. A visit from Queen Victoria in 1844 prompted the building of a Royal Arch to commemorate the occasion. The Arch, completed in 1848, became another landmark in the dock area.

When S.S. Camperdown set sail in 1861, Dundee’s port was busy with ships. As well as whaling and sealing ships, there were ships transporting raw jute from India, importing and exporting other goods, passenger boats linking Dundee to Leith and London, and more.

By the 1960s, however, the docks had quietened down once again. The growth of road and rail infrastructures meant that shipping was a less profitable way of transport for both goods and people. Whaling voyages to the Arctic had stopped decades earlier, and the shift of jute production from Dundee to India (though still by Dundonian firms) meant that jute was no longer being brought into the docks at anything close to its previous volume. In the run up to the construction of the Tay Road Bridge, Earl Grey and King William IV docks were closed and filled in. Victoria Dock is still there, although now closed off to the river, and is currently home to the historic ships HMS Unicorn and the Abertay Lightship, as well as a water activity park.

The filled in docks have been redeveloped once again in the 21st century and are now home to Slessor Gardens, where an outline in the paving stones marks the former location of the Royal Arch. It is likely the coming decades will see more change to the waterfront. The Sustainable Dundee website gives more information about how climate change might affect Dundee in the coming years and includes a link to the Climate Central Coastal Risk Screening Tool, which shows areas at risk of flooding if sea levels continue to rise at their projected levels. Several areas of reclaimed land near Dundee city centre may fall within the annual flood level by 2050, including Riverside Nature Reserve, the airport and railway station, and V&A Dundee and Discovery Point. Explore the predictions, and what we can do locally to help mitigate them at: www.sustainabledundee.co.uk/how-will-climate-change-affect-dundee.

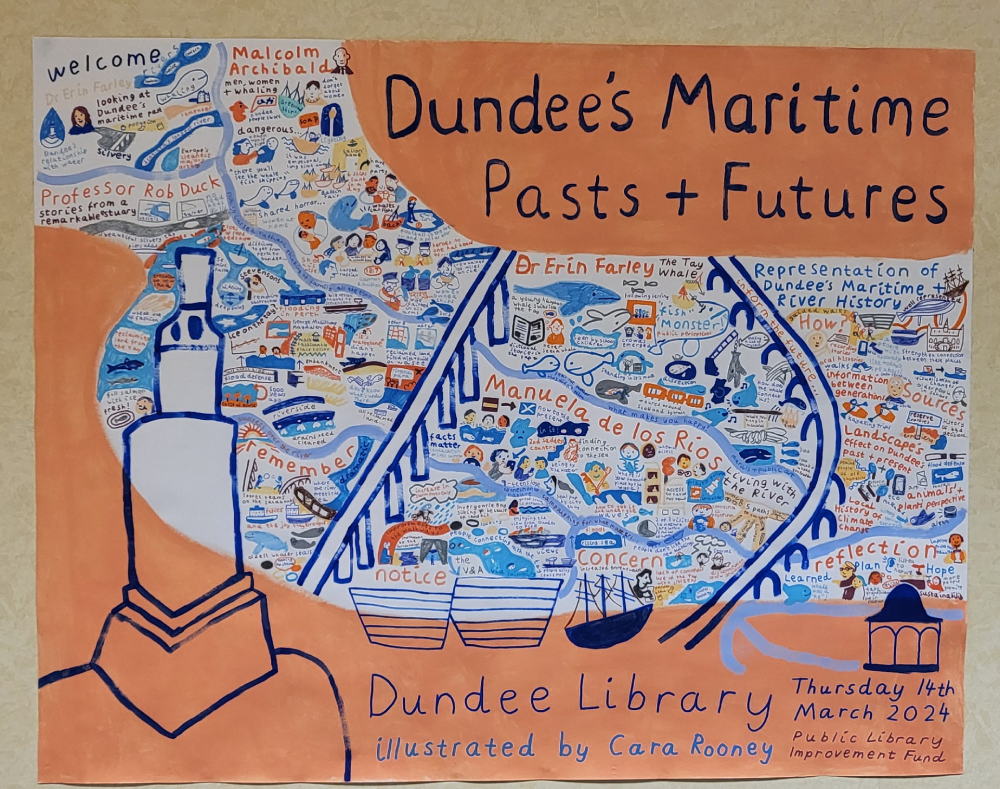

Maritime Pasts and Futures artwork by Cara Rooney

On 14 March 2024, we held an event in Central Library. This featured talks from Malcolm Archibald on the history of Dundee whaling, Professor Rob Duck on the geography of the Tay valley, Erin Farley on the Tay Whale and Manuela de los Rios on the benefits of living with rivers. In between talks, we asked participants to share their thoughts about the Tay: their memories, hopes, fears and plans. The artist Cara Rooney created an illustrated record of the day, which you can explore here.

This Project is supported by the Scottish Government Public Library Improvement Fund